ROELAND VAN OSS, THE BIKING TRAILBLAZER

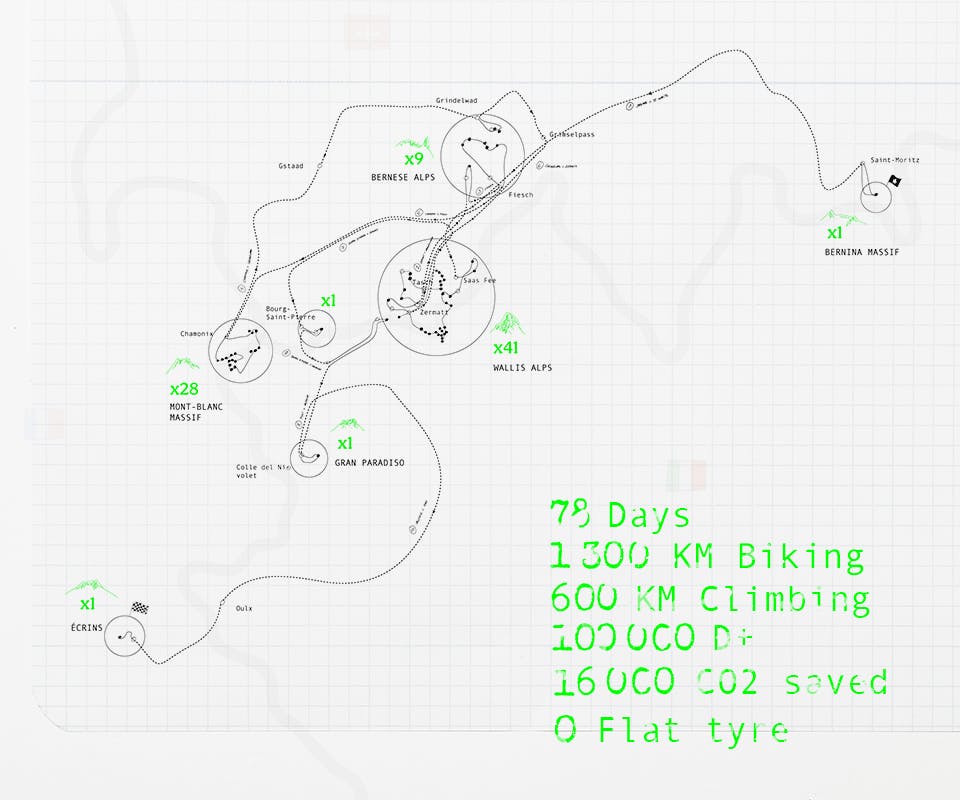

The ‘82 4000s’ of the Alps in 78 days, using only leg power and pedals

INTRODUCTION :

More than just a mountain guide, Roeland Van Oss is a trailblazer. More than simply an adventure, he successfully completed an epic challenge. More than just climbing the 82 peaks of the Alps sitting at over 4000 m above sea level, the 44-year-old Dutchman, now based in Chamonix, delivered an important message. Between May 27 and August 12, 2022, Roeland Van Oss successfully climbed the ‘82 4000s’ using only the power of his legs. How did he do it? By leaning hard on his convictions and pushing hard on the pedals. Why did he do it? To raise awareness of climate change and its impact on the job he does every day in the mountains.

The amazing exploit of an ordinary man, the trip produced extraordinary figures: 78 days, 1,300 km of cycling, 600 km of mountaineering and 100,000 m of elevation gain! The story of a once-in-a-lifetime project that had a huge impact on one man and contributed to changing attitudes.

“More than just a mountain guide, Roeland Van Oss is a trailblazer.”

“Pressing hard on the pedals. Leaning hard on his convictions.”

A NATIVE OF A COUNTRY WHERE THE HIGHEST POINT IS 322 METERS ABOVE SEA LEVEL

“There are only 10 mountain guides in the Netherlands. I’m number 7. That’s a very low ratio for the 16 million inhabitants of my native land, but it can be explained by the geography of the country, where the highest continental point, the Vaalseberg in South Limburg, is only 322 m above sea level. But I’m not complaining! It means there’s lot of work for us Dutch guides, with a large clientele of enthusiastic mountaineering compatriots who we can share out between us.”

“There are only 10 mountain guides in the Netherlands. I’m number 7.”

AN UNUSUAL ROUTE TO BECOMING A GUIDE

“The call of the mountains dates back to the summer hiking I did with my parents in the Alps. When I was 15, I joined the Dutch Alpine Club. This introduced me to the pleasure of exploring glaciers and I took part in several mountaineering races. I loved it. At 21, I became a sports teacher; and then a ski instructor for five seasons in Austria, followed by three more in France. It was during this time that I also fell in love with rock climbing. I then came to the conclusion that the best way of combining my three passions was to take the entrance exam for the mountain guide training scheme. I passed the exam at the age of 32, after two years dedicated to carrying out the famous ‘list of tests’.”

“At 21, I became a sports teacher; and then a ski instructor for five seasons in Austria, followed by three more in France.”

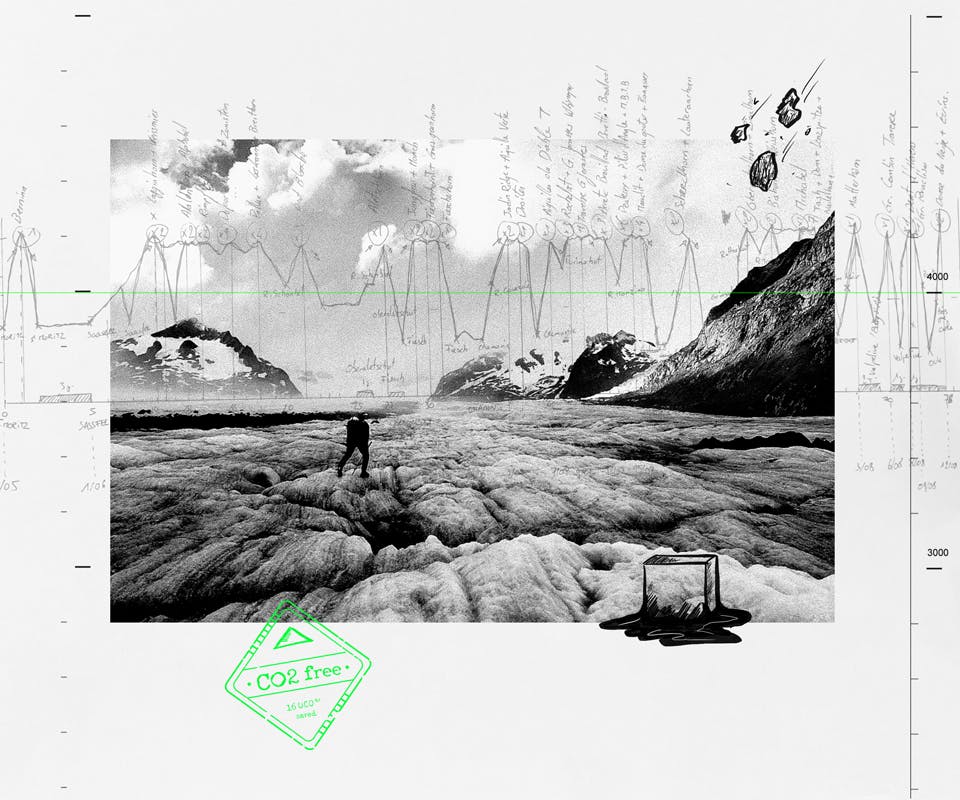

THE ORIGINS OF THE ‘82 x 4000s’ PROJECT? A SHOCKING OBSERVATION & A PROFOUND DESIRE

“My desire to climb the 82 peaks of the Alps over 4000 m without using any motorized forms of transport and relying solely on the strength of my legs, sprang from two sources. The first was a dramatic observation I made on my expedition to the Himalayas in 2021. At the foot of Everest, I realized that many people were there for performance reasons. They had only one goal: to be the first, the best, or the fastest... As I wandered round Europe, the desire to climb the ‘82 4000s’ grew in me. The observation and the desire then intertwined and this gave rise to the project. But rather than drawing attention to me – by shouting everywhere, ‘Hey, look what I’m doing!’ – I wanted to make this adventure an opportunity to raise awareness of an issue that’s close to my heart: climate change, and the way it impacts on our job as guides, us, the people who are the mountain trailblazers, permanently on the ground, in contact with the elements.”

“At the foot of Everest, I realized that many people were there for performance reasons. They had only one goal: to be the first, the best, or the fastest...”

METICULOUS PHYSICAL, MENTAL & LOGISTICAL PREPARATIONS

“This project was a long time in the making! It took me more than 6 months to set it up, what with finding sponsors and climbing partners, the physical and mental training, the logistical organization, the construction of a logical overall itinerary and the detailed analysis of each climb. I’d already climbed 50 of the 82 summits on my list, which meant I had valuable knowledge of the terrain. I made sure my physical training was extremely thorough, with 50% coming from my work as a guide in the mountains with my clients; the remaining 50% was more targeted with lots of trail running and steep 1000 m climbs weighed down with a 20 kg bag. Last but not least, in terms of mental preparation, I minimized stress by devising a plan B for each ascent. Having multiple options and “just in case” emergency exits was psychologically reassuring.”

“My physical training consisted of lots of trail running and steep 1000 m climbs weighed down with a 20 kg bag.”

TWO MAJOR DIFFICULTIES!

“The main issue, and the key to success in a way, is adaptability! You can make the best preparations in the world, but at certain points, it’s only the truth of the terrain that does the talking. The hardest thing is the permanent uncertainty linked to the weather, which forces you to constantly adapt your route plan. You’re so dependent on conditions that you’re constantly on the lookout for favorable windows to make, unmake and remake your plans. This creates a mental burden that weighs more and more heavily as the days go by. After a difficult ascent, normally you can let go and relax. But in this case, you have to stay super-focused because you’re already thinking about and planning for the next one. The other major difficulty was the heatwave at that time. Certain routes became very dangerous in the soaring temperatures. Glaciers were moving and landslides increasing. And all of this, of course, a direct result of climate change.”

“The hardest thing is the permanent uncertainty linked to the weather, which forces you to constantly adapt your route plan.”

“Certain routes became very dangerous in the soaring temperatures.”

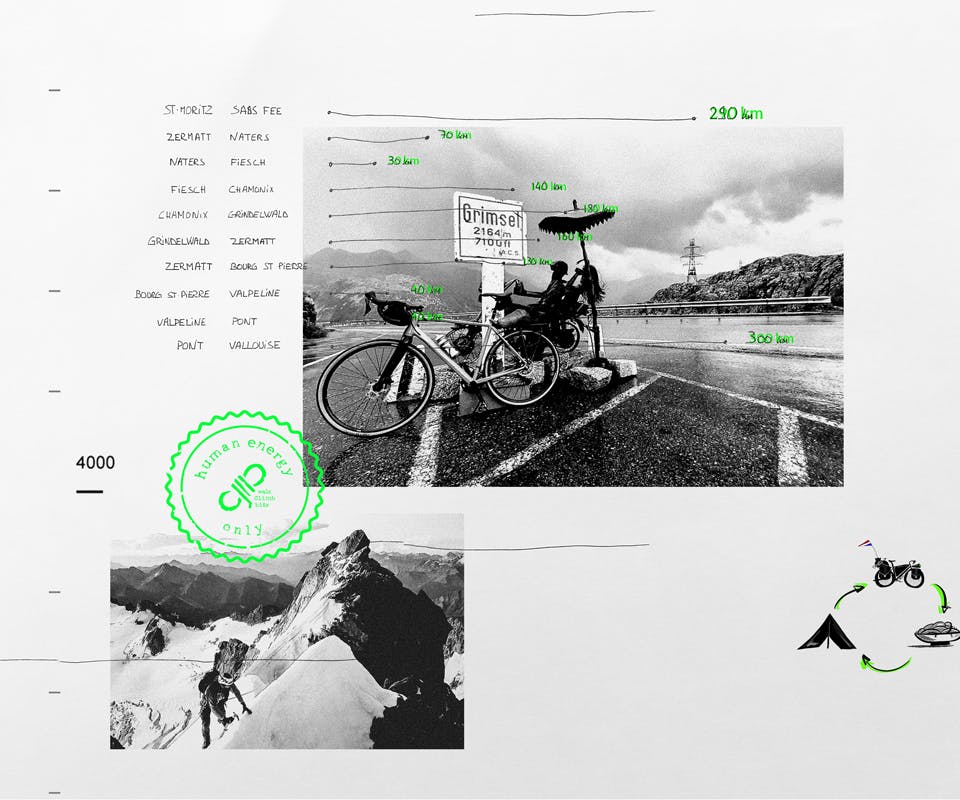

RIDE, EAT, SLEEP: SIMPLE BUT EFFECTIVE LOGISTICS

“For those 78 days, I carried my tent on a little trailer attached to my bike! This gave me the freedom to stop at any campsite I fancied to spend the night. In the high mountains, I slept in refuges which were sometimes no more than simple huts. For food, I was lucky in that I had to go back down into the valleys to join up the different climbs by bike. This gave me the opportunity to eat well, wherever I wanted. I lacked for nothing and ate my fill. I replenished my energy levels whenever it was necessary. I didn’t even lose any weight, unlike expeditions where you spend several weeks in a base camp. I don’t know how many plates of pasta I ate, but it must be kilos! I also feel a bit nostalgic for the protein chocolate milkshakes we sipped between two summits to aid our recovery. They had the fine flavor of satisfaction!”

“I lacked for nothing and ate my fill. I replenished my energy levels whenever it was necessary. I didn’t even lose any weight!”

“I also feel a bit nostalgic for the protein chocolate milkshakes we sipped between two summits to aid our recovery. They had the fine flavor of satisfaction!”

(ALMOST) NEVER ALONE

“Out of the ‘82 4000s’, I only climbed 4 solo. This shows just how much the project was a group endeavour and how much support I received! I was accompanied by 5 different climbers over the whole trip, some of whom stayed with me for almost 3 weeks. I managed to create these climbing parties by word of mouth – which allowed me to meet friends of friends who were keen to take part – but also, quite simply, by posting on social media.The power of this human adventure and the sharing surprised me. It was really amazing! I experienced a huge wave of solidarity and kindness.”

“Out of the ‘82 4000s’, I only climbed 4 solo.”

A PROJECT THAT CHANGES A LIFE, AND A MAN

“This project made me develop as a man. It changed my life and my perception of things. Firstly, I realized I was much stronger than I thought, that I had many more physical and mental resources than I’d given myself credit for. When people ask me what I’d change if I had to do it again, I say two things: firstly, I’d hire a communication professional to manage my social media and press relations; and I’d try to go even faster because it’s the length of the adventure and not its intensity that ultimately generates the most fatigue. The longer the project went on, the harder I found it to stay engaged mentally. As a result, when I finished, I felt two emotions: a huge amount of joy, followed by a deep sense of relief!”

“I realized I was much stronger than I thought, that I had many more physical and mental resources than I’d given myself credit for.”

“I’d try to go even faster because it’s the length of the adventure and not its intensity that ultimately generates the most fatigue.”

A MOUNTAIN TRAILBLAZER

“The one and only goal of the ‘82 4000s’ was to raise awareness of climate change. And how it impacts the mountains and therefore our profession. During the project, I could see at close hand how the glaciers are visibly melting, how heat and drought make climbs more and more dangerous, especially because of landslides, falling rocks, crevasses and so on. For example, on our final ascent to the Barre des Écrins, although it’s down as an easy route, no mountaineer had ventured there for more than 2 weeks because the conditions had made it so perilous. To conclude, I also observed a highly symbolic but worrying warning sign: ibex frolicking at more than 4000 m of altitude! The poor animals are forced to go up this high to find cooler temperatures...”

“For example, on our final ascent to the Barre des Écrins, although it’s down as an easy route, no mountaineer had ventured there for more than 2 weeks because the conditions had made it so perilous.”

“I also observed a highly symbolic but worrying warning sign: ibex (mountain goat) frolicking at more than 4000 m of altitude!!”

AN ORDINARY MAN AND SOME HERCULEAN FIGURES

0 punctures in 1,300 km of cycling

600 km traveled on foot through mountaineering

100,000 m of elevation gain

78 accompanied summits, only 4 solo

A 25-hour route on the longest day to traverse ‘7 4000s’

16,000 kg of CO2 carbon footprint saving

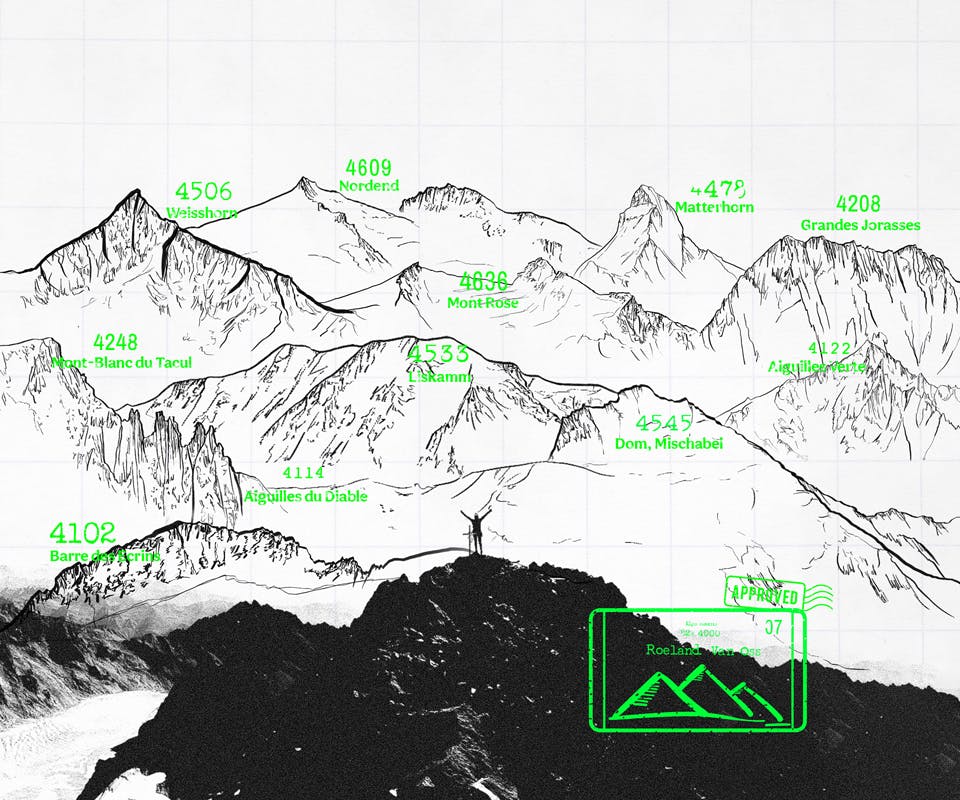

THE MOST STRIKING ‘4000s’

The first 4000: Piz Bernina

“May 28th. I chose it as the starting point because from here it’s easy to then go to Zermatt and Saas-Fee in Switzerland, a region with many peaks over 4000 m.”

The last 4000: the Barre des Écrins

“One of the most remote and one of the most isolated. It was a strategic choice to end up at this one because it’s supposed to be easy and you don’t then have to cycle a long distance to another valley.”

The most esthetically pleasing: the Arête du Diable, to get to Mont-Blanc du Tacul, and the north face of the Weisshorn

“I can’t separate them in my mind. I’d already climbed the two summits by their normal route in the company of clients, but never via these absolutely stunning variants.”

The most surprising: the Schreckhorn traverse above Grindelwald

“I was amazed by the hardness and special quality of the rock.”

The one you’d like in your garden so you could climb it every day:

“Oh wow! (After a long pause) The Weisshorn, I think. The north face is sublime. It’s the perfect combination of everything a mountaineer could wish for: the quality of the snow, the purity of the rock and the beauty of the landscape...”

The easiest: the Bishorn

“We got there so fast it felt like we’d flown up it... In just 2 hours it was done!”

The longest: the Dent d’Hérens

“This was the ascent that took us the longest! But the longest day was July 31st: 25 hours to do the whole skyline above Zermatt. ‘7 4000s’ all in one go! A traverse of ‘Tasch – Dom – Lenzspitze – Nadelhorn – Stecknadelhorn – Durrihorn – Hohbarghorn’. Definitely a hard day at the office!

The hardest: the Grandes Jorasses

“A myth that deserves its legendary status.”

The most technically challenging: the Arête du Diable

“A fraction less hard than the Grandes Jorasses in terms of physical and mental commitment, but very difficult from a technical point of view.”

The scariest: the Dent d’Hérens

“They were all made terrifying by the extremely dangerous conditions. Even the supposedly easy Barre des Écrins was frightening... But the Dent d’Hérens, with its open and highly unstable glacier, was even more so.”

The favorite cycling pass: the Colle del Nivolet

“The pass that takes you to the Gran Paradiso National Park. A 38 km ascent and almost 2000 m of elevation gain, followed by a 40 km descent with breathtaking views of a magnificent Italian valley.”

The most grueling mountain pass: the Col du Pillon

“A pass in the Swiss Alps that isn’t necessarily feared for its extreme difficulty but still pushed me right to my limits. It was almost 40°C. I was zigzagging all over the road until a car pulled over to tow me. I kindly declined, replying that I couldn’t take up the offer: I’d promised myself I’d complete the ’82 4000s’ project using only the power of my legs!”